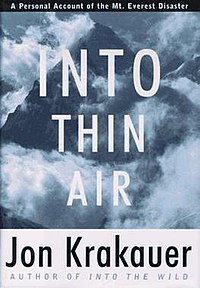

Into Thin Air

Jon Krakauer

1997

USA

“As I gazed across the sky at this contrail,

it occurred to me that the top of Everest was precisely the same height as the

pressurized jet bearing me through the heavens. That I proposed to climb to the

cruising altitude of an Airbus 300 jetliner struck me, at that moment, as

preposterous, or worse.”

Most

of us spend our lives seeking comfort. I am no exception. So it was a little

weird to read this book while worrying about what furniture would look best my

new apartment, and how to arrange my things in the most aesthetically pleasing

way. In a way it made life easier for me, because the people I was spending

time with during my reading hours were freezing and sick and gasping for air up

on an unforgiving mountain, and so my little apartment without air conditioning,

in comparison, seemed downright luxurious.

Into Thin Air is a non-fiction book

about the tragedies that occurred during climbing season on Mt. Everest in

1996. You may have heard of it; it was a bestseller. The author, Jon Krakauer,

is an amateur climber, but his primary role on the Everest expedition was

supposed to be as a reporter (he had originally intended to remain at Base

Camp, but the allure of the summit was too much for him and he ended up

climbing to the top, too). Commissioned by Outside

magazine, Krakauer was to write an article assessing what many “purist”

climbers referred to as the “commercialization” of Everest. He does a good job

of filling us uneducated readers in on the argument between people who believe

that only those who are able to climb without the aid of a paid guide should do

so, and others who see no problem with Everest being run as a kind of extreme

amusement park (there is a secondary debate, too, about whether using

supplemental oxygen to reach the summit is cheating or not). Krakauer wrote his

article for Outside immediately after

returning from Everest in 1996, but found that he could not put the experience to

rest. Twelve people had died, and Krakauer and many of the other climbers were

still struggling to understand why. The book is the result of its author’s need

for clarification, insight, and meaning. It attempts to offer the same to its

readers and, at its best moments, succeeds.

I

haven’t read many “adventure” books, so I won’t pretend to be an expert on the

genre. However, the type of tone and content that I would have expected from

such a book was completely missing from Into

Thin Air. Instead of larger-than-life characters, Krakauer seeks to

humanize every person he meets on the mountain that spring. The reader is left

with an impression not of heroic, impossibly strong mountaineers to be admired,

but instead of real, often weak, eminently human men and women, attempting to

summit the world’s tallest peak for a host of reasons, some more admirable than

others. There are depressingly few moments of romantic vistas and awe-inspiring

natural scenery; the few there are are almost completely outweighed by

descriptions of dirty, festering camps, aching muscles and heads, broken bodies

left behind in the snow, and the cruel ice, wind, and snowdrifts of Mt.

Everest. There’s no doubt that the results of the climb soured Krakauer’s view

of the entire experience, but it was fascinating to read a book written by

someone who admittedly loves (loved?) climbing told in such a dark, almost

angry tone.

Other climbers

who were there that spring have since denounced Krakauer, claiming that his

version of events is not entirely true (mostly this has come from one of the

guides who believes Krakauer painted an unfairly negative portrait of him).

Clearly, I don’t know whether what

Krakauer writes is 100% “true” or not, but I am convinced that he is reporting

to the best of his and others’ knowledge. He seems desperate to find the truth

at whatever cost to himself or others’ views of themselves, and I find that

convincing evidence of his impartiality. Krakauer wants to know why, but not so

badly that he twists the story to create a clear-cut, specific reason that

explains it all. Instead, he tells what happened, moment by moment and day by

day, and we must decide for ourselves along with him about what went wrong.

One of Krakauer’s

central claims seems to be that the accidental deaths that occurred on his trek

to Everest were not, contrary to popular belief, all that unusual. “If you can convince

yourself that Rob Hall [the expedition’s leader] died because he made a string

of stupid errors and that you are too clever to repeat those same errors, it

makes it easier for you to attempt Everest in the face of some of the rather

compelling evidence that doing so is injudicious. In fact, the murderous

outcome of 1996 was in many ways simply business as usual. Although a record

number of people died in the spring climbing season on Everest, the 12

fatalities amounted to only 3 percent of the 398 climbers who ascended higher

than Base Camp – which is actually slightly below the historical fatality rate

of 3.3 percent.” Perhaps it should seem obvious to us that climbing the world’s

highest peak is a life-threatening task. But, this late in the game, I think

many of us have the sense that if we pay enough for something (and the people

on Rob Hall’s expedition paid upwards of $65,000 for their opportunity to reach

Everest’s summit), and if we are important enough (there were many, many

doctors and a minor celebrity upon the mountain that spring) then we simply won’t

die from taking an extreme vacation. It seems like there are safety precautions

in place for everything; planes can fly anywhere, and if something goes wrong,

we will sue somebody. Into Thin Air

reminds us that sometimes things go wrong anyway, and that sometimes there isn’t

any one person or company at fault; sometimes you just have to live with death.

It turns out there are still are places that are truly wild, and untamable. I

guess that’s why people go out there to seek them, to find those places where

all bets are off, where it isn’t necessarily going to be okay, where every tiny

movement you make is the difference between life and death. I can understand

that, I think. It’s something primordial, a desire to be back at the beginning,

when it was just man and woman vs. wild, and all of these other, silly, side

issues, like how many people are reading our blogs and whether or not we

impressed our boss, didn’t even exist. When you’re focused on survival, you can

finally let all your other cares go.

A

quick Google search of “climbing Mt. Everest” reveals that despite the danger,

people are still interested in reaching the summit. Call me crazy – and there’s

no way I’m ever trying to go to the top – but this expedition to Everest Base

Camp sounds pretty good: http://www.akextremeadventures.com/adventure-travel/expedition/mount/everest/base-camp/trek/packageID/5208?did=5199&jt=1&jp=&jadid=10539367819&js=1&jk=climb%20everest%20expedition&jsid=24506&jkId=gc:a8a8ae4e72f9eb09d012fa532374a69b3:t1_b_:k_climb%20everest%20expedition:pl_&&gclid=CLzGsMnF07ECFYeo4AodMkkA0Q.

30th birthday trip, perhaps? ;)

No comments:

Post a Comment